Solar activity typically follows an 11-year cycle but longer-term patterns stretch across decades or even centuries. From the 1980s through to 2008, sunspots and solar wind weakened to record lows, leading many experts to believe the sun was heading into a historic lull. Instead, it reversed course.

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, suggest Earth could face more space weather events in coming years, including solar storms, flares and coronal mass ejections.

“All signs were pointing to the sun going into a prolonged phase of low activity,” said Jamie Jasinski, lead author of the study from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. “So it was a surprise to see that trend reversed. The sun is slowly waking up.”

Astronomers have tracked solar behaviour since the early 1600s, beginning with Galileo’s sunspot records. Sunspots – dark, cooler patches on the sun’s surface caused by intense magnetic activity – are often linked to higher solar activity. They can trigger bursts of radiation known as solar flares and vast ejections of plasma that travel through the solar system.

These events, collectively known as space weather, have real-world impacts. They can disrupt satellites, radio communications, global positioning system and power grids, and pose risks to astronauts. Monitoring and predicting solar activity is also crucial for upcoming space missions, such as NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the moon and eventually reach Mars.

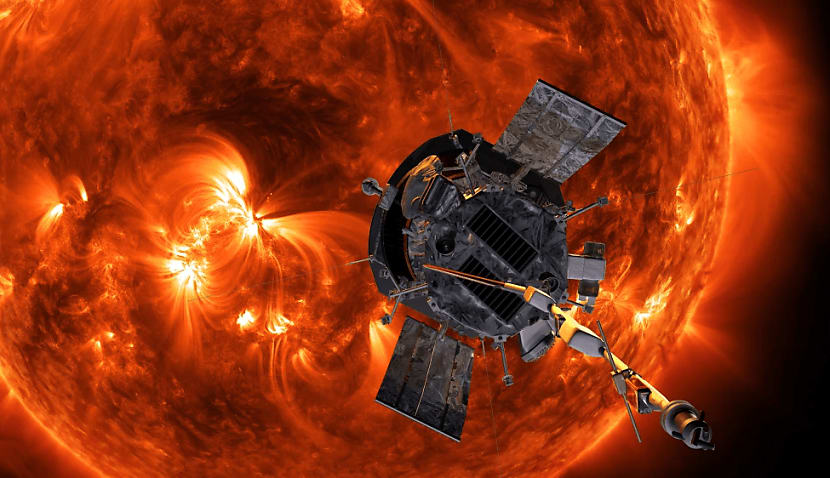

NASA will soon launch a series of spacecraft to improve space weather forecasting. The IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe), the Carruthers Geocorona Observatory, and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s SWFO-L1 (Space Weather Follow On-Lagrange 1) mission are all due to lift-off no earlier than 23 September. These missions will provide fresh data to help scientists understand the sun’s changing behaviour and its effects across the solar system.

Solar activity influences planetary magnetic fields, which act as protective shields against the constant flow of charged particles known as the solar wind. When the sun is more active, these magnetospheres can be compressed, altering their protective capacity, a factor that matters not just for Earth, but for all magnetised planets.

Historical records show the sun has gone through long stretches of minimal activity before, including the so-called Maunder Minimum between 1645 and 1715, and another quiet spell from 1790 to 1830. Why these deep lulls occurred remains uncertain.

“We don’t really know why the sun went through a 40-year minimum starting in 1790,” Jasinski said. “The longer-term trends are a lot less predictable and are something we don’t completely understand yet.”

The new study relied on decades of heliospheric data, much of it collected by NASA’s ACE (Advanced Composition Explorer) and Wind spacecraft, which have been monitoring solar particles and magnetic fields since the 1990s. Their observations form part of a wider fleet of NASA missions dedicated to understanding the sun and its influence on Earth and beyond.

With solar activity now climbing again, scientists are watching closely to see how this new phase unfolds and how it might affect technology, astronauts and even life back on Earth.